Joe Sinness: The Flowers

Review by Molly Davy

Minnesota Artists Exhibition Program (MAEP)

Jul 20–Oct 29, 2017

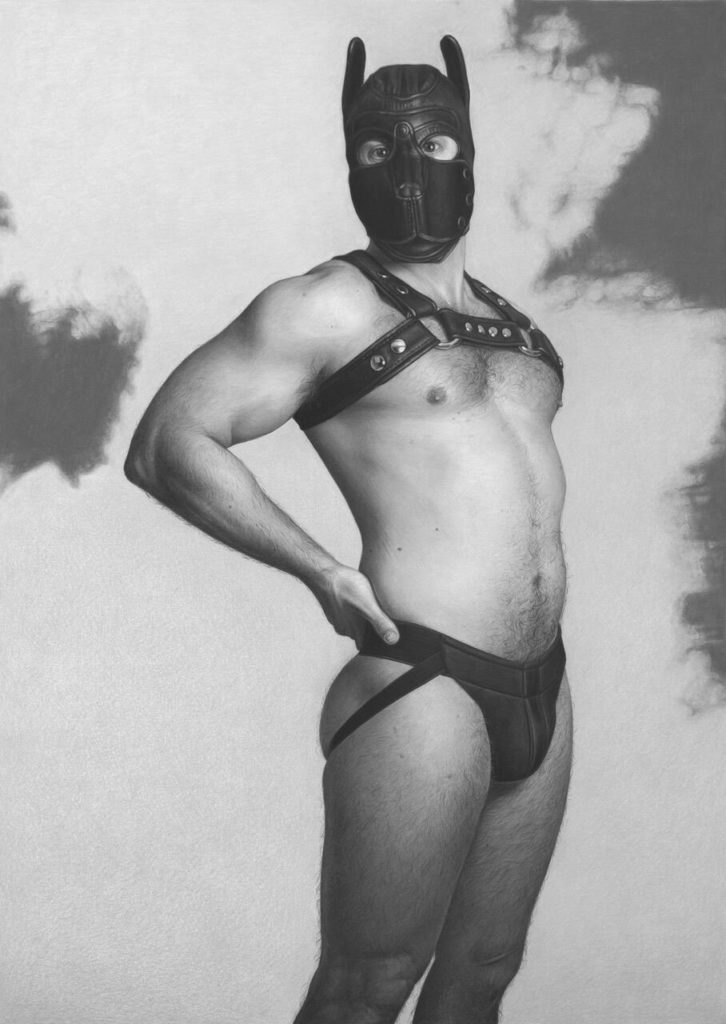

Joe Sinness transforms a gallery of the Minneapolis Institute of Art into a hyperrealist staging of queer desire in his recent exhibition of sculptures and drawings. “the Flowers” challenges fixed notions of queerness with the variety of works in subject and medium championing the expansiveness of gender, depicting it as something resistant to the confines of categorization.

Queer culture was born, in part, out of an intimate, underground language of codes and signals, fashion choices and haircuts. Gender theorist Judith Butler frames queerness as a performance,1 and Sinness echoes this in a series of colored pencil portraits, harkening back to the pre-photograph, oil portraits of the Old Masters. In Contemporary Art, this brings to mind the work of Kehinde Wiley, a queer-identified man, whose opulent portraits of young black men have hung in tandem with portraits of White European royalty in Mia’s galleries in its past installation “Art: Re-Mix.”

A reinterpretation of historical art motifs with contemporary cultural references emerges as a pattern throughout these works. Sinness re-imagines a still excerpted from William Friedkin’s 1980 film Cruising in a moody blue colored pencil panorama drawing hung above a stark, metal urinal. Sinness’ reference to Cruising questions the subjective lens of the straight, cisgendered Friedkin and his self-designated sense of authority in depicting gay masculinity. The set piece of a men’s bathroom is displayed in this context as both a historically popular setting for queer desire, and a politicized space of gender and trans identity, ultimately producing a challenging diptych of queer narratives.

In a political climate of precarity, the subjects in Sinness’ portraits and sculptures claim desire for each other, for representation in the institutional space they inhabit, and in society as a whole.

Queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz cites queerness as something that has not yet arrived, as “that thing that lets us feel that the world is not enough.” 2 Sinness’ careful rendering of his subjects, particularly in his time-consuming colored pencil portraits with rich colors and brightly patterned backgrounds, create a feeling that they are standing right before you. But they are also elevated into a different world, a much better one, one we hope to reach.