MATERIAL MYTHOLOGIES

Review by Kari Mugo

Minnesota Museum of American Art

Mar 11–Apr 3, 2016

I. Memory

Artist Sonya Clark’s work, featured as part of the Material Mythologies exhibit at the Minnesota Museum of American Art (MMAA), is as much about myth as it is about history. Her pieces, entangling themselves in a playful exploration of hair and memory for those of us of African descent – asked questions of questions. The construction of not one, but two pieces in the collection, around fine tooth combs is a wink and elbow jab at our kinfolk – in what ways have we loaned our histories to these inanimate objects? What does it mean to remove them from their functionality and imagine them as other?

Clark’s Triangle Trade was the most effusive piece of her work featured. Drawing me in, while inspiring the memory of my life-long aversion to centipedes. Or any myriapoda for that matter. Scurrying beneath the dirt and across cold bare walls in the basements of houses, only to freeze under the harsh fluorescent overhead light when they are discovered. I freeze too during these grim encounters. Frightened by the wealth of knowledge that lays in each of these creatures’ limbs. Limbs that themselves appear divided into a multiplicity of moving parts, carrying them across the great expanses of their universe… and mine. If you can understand that feeling, that grappling with something terrifying, yet undeniably real, then you too would understand what it feels like to stand in front of Clark’s Triangle Trade and stare at the great expanse of lives spent in the pursuit of capitalistic endeavors. Clark’s tremendous canvass, a tribute to the most perfectly executed example of triangle trade – the transatlantic slave trade – is interrupted by black cotton thread woven through as one would braid a child’s hair at the start of a hot summer; carefully and intricately, braiding each strand into the next. It’s dizzying to watch the black threads come together, and pull apart…. together….apart.

And if you stare long enough, the strands cease to be a pattern on canvas. The broken backs, stretched against their will become undeniable, the mass of bodies mobilizing to turn the cogs that bind them in a never ending cycle of flesh for profit glare back at you. Clark’s Afro-caribbean history lending to the poignancy of these intertwined narratives asks questions about her, and our own, place in history.

II. Five Women.

Few things are more appealing than a museum space dedicated to women’s work. Few things are even more appealing than a museum space dedicated to women’s work that primarily features the work of women of color. Clark, Teri Greeves, Helen Lee, and Jae Won Lee bring with them their rich cultural backgrounds, while Minnesota’s own, Mary Giles rounds them out with the deft precision of an artist who knows her trade and materials; sculpture and metal. Featuring Giles’ work in the promotional materials surrounding this exhibit is deceitful, however. Giles’ sculptures, while outstanding, do not rival the depth of exploration of memory, loss, ancestry, meaning, and belonging that Clark, Lee, and Won Lee distill in their different works.

Take for instance, Won Lee’s Sleepwalking in the Peach Garden that is an ethereal walk in a distant land. Won Lee, constructing and deconstructing, cuts across the origami paper lines to build her own shapes. Suspended from handfuls of colorful strings, her Peach Garden greets you at eye level, affording you the opportunity to walk around it and under it, as it sways under the weight of the spoken words around it. Not to mention Won Lee’s other striking sculpture, Layers of Mountains, that uses flowers petals collected over time and pressed into porcelain to construct her longing for home.

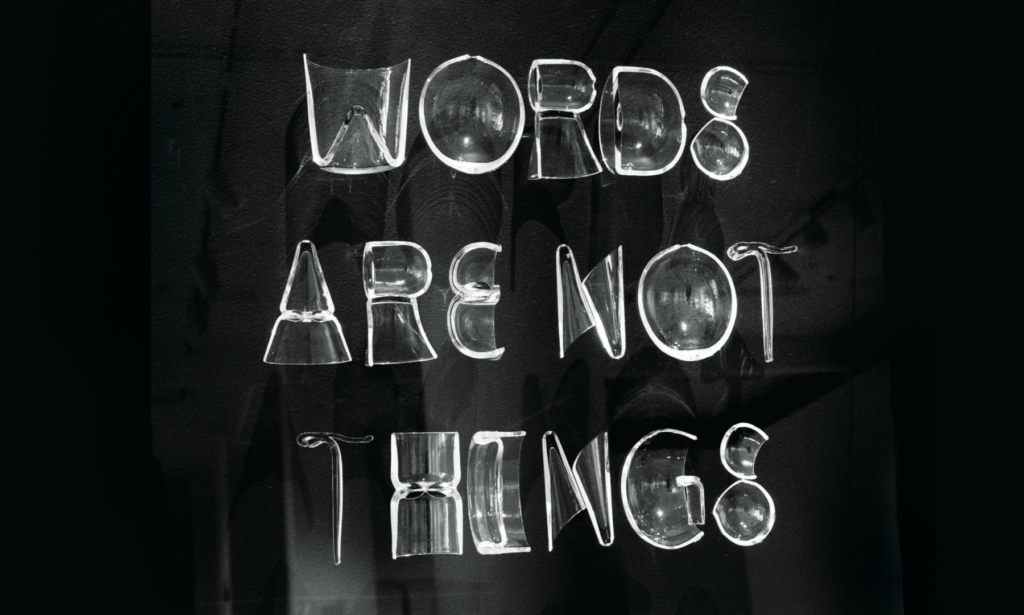

Then there is Helen Lee’s contribution to the exhibit, challenging our notions of language as she encapsulates the said and unsaid things in glass. Lee’s ‘WORDS ARE NOT THINGS’ smirks back at you in a hand blown relief as you enter the gallery. And tucked in the back is her Pillow Book, holding within it the countless dreams of others. Following a period of deep unrest, a time when Lee couldn’t sleep, she sought out the dreams of her friends and family. Layer by layer, she inscribed them onto her Pillow Book – the result is a series of sleepless nights, illegible now, as they were then.

Unfortunately for Terri Greeves, the fifth woman featured in the exhibit, her work was muted from the larger discussion evoked by the other women’s work. Sonya Clark, Helen Lee, or Jae Won Lee’s works would have been more fitting as visual representatives of the entire exhibit, given the unifying narrative across their work – each raising questions on place and memory. Which lends to the question of whitewashing within the arts – where artists of color are either relegated to singular rooms within museum spaces, or required to qualify their art as “other” first and “art” second. That an exhibit exploring contemporary craft and sculpture featuring the work of four women artists of color would still choose to brand itself on the singular white artist’s work confounded me.

As I did another loop of the space, looking for the little things I had failed to see, the gallery began to fill up. I deliberated staying for the 3 p.m. gallery talk hosted by American Craft Magazine’s Editor in Chief and the MMAA’s Curator of Exhibitions and Public Programs, but it’s a strange feeling when in a room filled with the dreams of women of color, you still find yourself a minority. Before the seating arrangements could be made, I grabbed my coat and scurried out the front door, disappearing in the maze of Lowertown’s one-ways.