Postcommodity

Review by Damon Stanek

Bockley Gallery

Mar 10–Apr 15, 2017

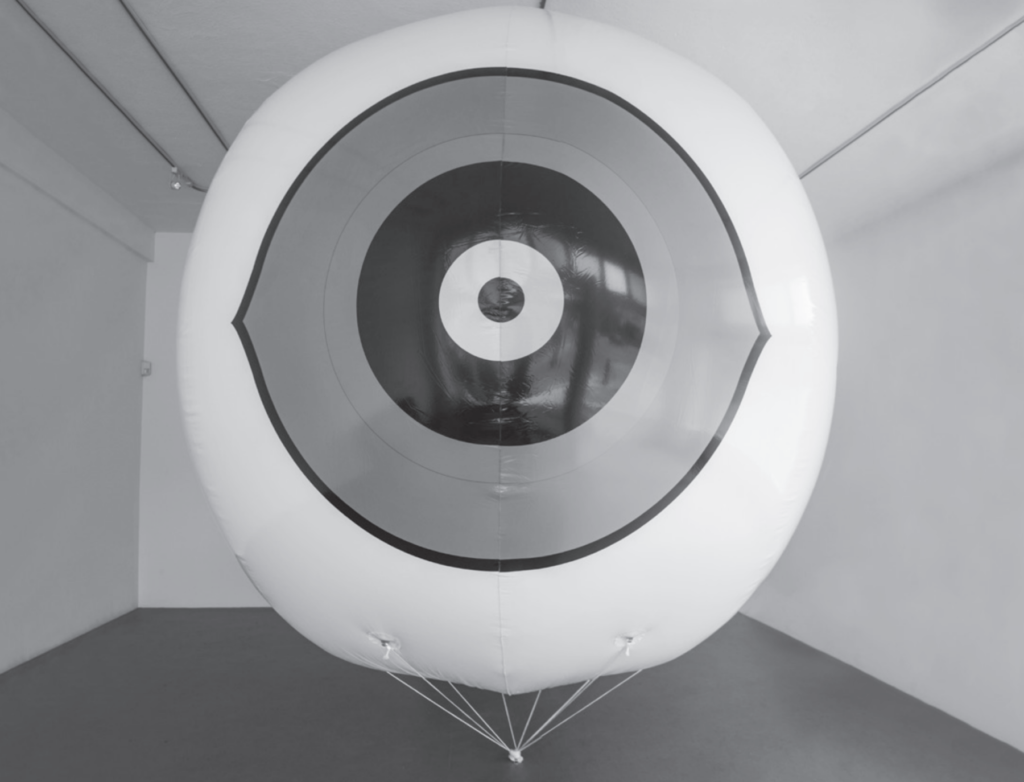

There is no missing the Bockley Gallery in the quiet Kenwood neighborhood. A very large balloon floating in the main gallery makes the space recognizable from far down the street. Upon entering, one engages in a subtle struggle for space—feeling a bit crowded toward the periphery by the brightly colored ten-foot balloon gently rocking against its floor tether.

The exhibition features three works by Postcommodity, an artist collective based in the Southwest. The current members (Raven Chacon, Cristobal Martinez and Kade L. Twist) traveled from their homes in Albequerque, Mesa and Santa Fe for the opening and to speak at the Walker Art Center in March. The trio’s upbringing is Navaho, Mestizos and Cherokee, and the concerns and stereotypes of these indigenous roots run deep within their work. As Chacon noted, their work seeks to subvert the fundamental impressions of indigenous art: that native artists are overly imprinted by identity issues, and that native art is principally craft based. Sound, along with other intangibles like video, have been central mediums for Postcommodity. The Bockley show seemingly offers an escape with three editioned works on display, none of which are beaded craft.

The balloon, entitled N12: 31°20’47.02”N; 109°29’47.62”W (2015), is accompanied by a large photographic print, and a monitor-based video of comparable size. Each work directly relates to Repellant Fence (2015), a site-specific work marked by both its ephemerality and bureaucratic perseverance. Postcommodity’s efforts, a line of twenty-six balloons like the one on display, crossed the Arizona border into Mexico and penetrated a full mile into both countries. The photograph documents the four-day installation, showing the border dividing the image even as the balloons pull our gaze past and toward the Sierra Madre Mountains.

Repellent Fence occupied the aesthetic space between the bureaucratic formalism of scale, site, and permissions found in Christo’s oeuvre, the tradition of land art, and the more-recent concerns over community engagement and social practice. But in the gallery, the trio of works convey little aesthetic shock of this complexity. Neither the big outdoor events of land art, nor the documenting images seem to challenge expectations, and the impact the communities contributed to these works is beyond our horizon. Documentation has long been our entry point to Michael Heizer’s deep cut into the Nevada desert, Walter De Maria’s acupuncture of the New Mexico high desert, and Robert Smithson’s spiraling rail-bed in Utah. Yet, unlike the first two, Smithson’s Spiral Jetty is not limited to its mud, salt-crystals, rocks, and water in a corner of the Great Salt Lake, rather Spiral Jetty circulates like his non-sites as drawings, photographs and a film—it is a portal allowing us to refocus and reconceive our spatio-temporal perceptions. Postcommodity slightly unmoors us with these works; one becomes like the gently drifting balloon. Our thoughts vacillate between imagining this land prior to the striations of political borders, the impact of these communities upon the land, and the short-term curiosity regarding helium and the balloon’s pvc structure: will it stay afloat for the run of the exhibition?

N12: 31°20’47.02”N; 109°29’47.62”W is big, it is happy, it is absurd. Around the waist of this bright-yellow balloon, four eyes mark the cardinal points. Their black, white, black, blue, and red rings replicate the ‘scare eyes’ of a Bird-B-Gone product—a device designed to frighten away birds and whose performance never lives up to it’s late-night TV commercial claims. Similar to a border wall?

In the photograph, these scare-eyes survey the border from both sides, but what is seen? Or now, what role do they play? Unlike the fence they drift above, these balloons present neither a barrier to the ancient migrations routes of indigenous peoples, nor divide regional inhabitants. They even fail to disrupt animal migration. They offer witness instead. Yet, one critique often leveled at post-conceptual art is its inability to speak for itself. Frequently a gallery press release offers the only contextualization to the viewer. Within the Bockley Gallery, severed from its original site, how does Postcommodity hope that I read this balloon? I struggle to recover the community engagement at the genesis of these works: to understand how the aesthetic decisions are shaped by peoples divided by politics and transnational economics, or even the appeal to media which circulate so ephemerally across our electronic devices.

The video 31°19’19.10”N; 109°29’47.62”W: And Golden Light has a subtle and destabilizing effect. A single balloon is shown drifting high above the desert at the end of its tether. It bobs slowly toand-fro, and as it eclipses the sun, this contemporary scareeye—a metaphor of surveillance and border politics—obscures the enlightening powers of the sun. It is as if the conservative politics or contemporary market forces mute the spiritual and enlightening power of indigenous tradition. An electronic drone provides the video’s score, it is a solar chorus we hear throughout the gallery, even if we are not actively listening. The stability of the tone varies just enough for the sound to have bite, it is at once both energizing and mildly menacing, not unlike an extended to exposure to the sun. Exposure is what the works on display achieve. It is our recognition, after a long afternoon in the sun, to the issues we have been exposed to and must treat with care.

The success of the work is dependent, in part, upon our willingness to engage in the discussions about the borders traversed by Postcommodity. As political constructions, borders have long been divisive wedges dividing lands and communities into an artificially generated here and there. Repellent Fence was able to bypass the impediment to renew the bonds between neighboring communities. But isolated from the other balloons, and at our remote distance from those communities, does the work’s potential still speak to us, or do we fall prey to the hectoring of the build-the-wall faction? To feel its effect, I think that this work needs to be seen within a crowded gallery space. We need the balloon, which failed to police the desert, to encroach upon our space in the gallery. We need it to force an active spatial politics with our small community. Postcommodity’s gallery exhibition marks a site where attitudes about the world can collide in debate, yet the balloon doesn’t crowd us so much that the debate cannot remain amicable.