Tanya Lukin Linklater: The Harvest Sturdies

Review by Christina Schmid

All My Relations Arts

Feb 26–Mar 5, 2017

Clip, scrape, wring, stretch, tan, smoke, wash: the verbs printed on white canvas tarp form a circle, leaving the center blank, as if to re-present that any listing of actions must necessarily fall short of the tradition such words aim to describe. Tanya Lukin Linklater, the first artist in residence at All My Relations Gallery, thus engages the making of moosehide mitts, astisak, a practice and product steeped in layers of cultural significance among the First Nations at home around James Bay, in Ontario, Canada. In the gallery, strands of sinew suspend five white banners that hang like the over-sized pages of a disassembled book and hold Lukin Linklater’s visual poems.

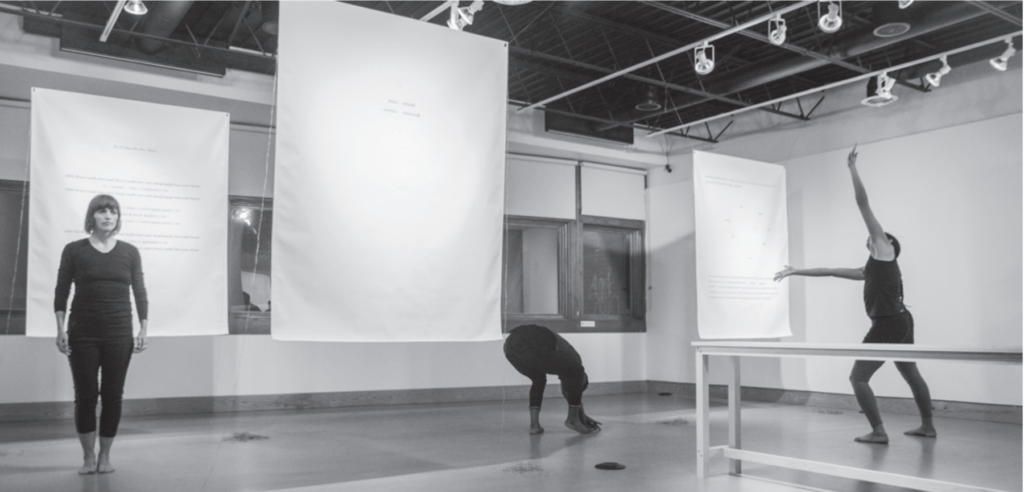

The Harvest Sturdies (2013), the collective title of the texts, alter the book form. Rather than a bound container of dark marks on white pages, Lukin Linklater’s pages structure a space and direct bodies to move in-between and among the rectangular pieces of tarp. As if to amplify this hint of choreography, Lukin Linklater collaborated with three local dancers, Jessika Akpaka, Sharon Picasso, and Lela Pierce. On opening night, they performed three cycles of a sequence of movements in the gallery, transforming the actions the poems describe into dance and interpreting the shape and meaning of the words as scores. Fingers gather invisible seams, arms stretch absent hides, a body pays silent tribute to the magnificent animals who gave their life. Rendered with care and precision, the gestures conjure absences that, once felt, insist on being present.

Gestures, writes Giorgio Agamben, resist finitude and thus trouble a neat separation into what was, is, and will be. This lack of finitude is of particular significance in the context of Lukin Linklater’s work. Inspired by ongoing struggles to maintain sovereignty, Lukin Linklater conceived of The Harvest Sturdies in response to Chief Theresa Spence’s 44-day hunger strike in 2012-13. Spence, who is associated with Idle No More and other efforts that emphasize the incompleteness of the North American colonial projects, is a member of the Attawapiskat First Nation. For many of her public appearances during the protest, she wore moosehide mitts, a brief essay in the gallery explains. The artist set out to learn more about the cultural significance of the moosehide mitts and the women, iskwewak, who traditionally make them.

Though her process bears a faint resemblance to ethnographic research, Lukin Linklater steers clear of scholarly protocol’s insistence on detached observation. Instead, she embraces a form of intimate, interested inquiry. Her interviews, transcribed, excerpted, edited, and arranged for poetic effect, serve as the seeds for The Harvest Sturdies. Speaking with relatives, in person and on the phone, the artist gathers knowledge through interactions and conversations. “So it’s done like this, Tanya,” one poem begins.

The collaborative gestures of her process extend into the gallery space where the text-bearing banners become potential movement scores for dancers and where her children’s stop-motion videos play. They, too, are part of the work, which does not end with objects and is not limited to studio time. Teresita Fernandez writes, “Being an artist is not just about what happens when you are in the studio. The way you live, the people you choose to love and the way you love them, the way you vote, the words that come out of your mouth… will also become the raw material for the art you make.” The title of another work, The Treaty is in the Body (2017), echoes such sentiments: treaty, the didactic explains, not only refers to legal agreements routinely violated in the history of North America, but to an ethos of sharing, generosity, and compassion held deep within the individual and collective body.

Yet while Lukin Linklater’s work clearly implicates the body, it is withdrawn from representation. With good cause: such images risk distortions and clichés that may supplant lived complexity. The silhouette of the “American Spirit” brand, the only representation included, is a case in point. The moosehide mitts, too, are present only in and as text. The objects themselves remain elusive. This gesture begs further questions: does the withdrawal evidence resistance to commodifying something so dear for the sake of art? Or does it hint at the fact that very few people remain who know how astisak should be made? “You say only three or four left in Peawanuck and perhaps two in Fort Severn know how to fix the hide of atik,” one of the poems says. The specter of possible loss looms large. Absence echoes in the space around the banners, on the white pages that hold the poems. ButThe Harvest Sturdies is no elegy for a vanishing culture: the body displaced and dispossessed is also the body capable of communicating beyond the limits of verbal language, is also the body that keeps the score of trauma and re-members while holding a space for resilience and survivance.

The Treaty is in the Body consists of two slender tables. Each holds a pale blue cigarette box of a hue that matches glass beads scattered on the wooden surfaces. Sewn into decorative patterns, beads like this would have been used in traditional James Bay moosehide mitts, the didactic informs. Yet here, their presence suggests pure potential, aftermath, or, quite possibly, both at the same time. Such non-linear temporality, a simultaneity of past, present, and prophesy, is key in stories passed from generation to generation: they do not occur in some ancient, mythical past but are ongoing, forever unfolding, shape-shifting and resilient the way survivors are. Such stories, passed on by communities reliant on oral traditions, dodge the definity of the written word. Instead, they charge the space between storyteller and recipient with performative possibility.

It is in this space that Lukin Linklater’s The Harvest Sturdies hang suspended like pages from a dissembled book; or hides stretched to dry; or tarps strung up for shelter. One of the poems rises like a column of smoke; in another, verbs circle a bare center. Black marks settle into patterns that stitch together meaning. Profoundly poetic and political, the work takes me toward the root of translation, where another verb, this one Latin, waits: transferre means to carry across, its past participle, translatum, denotes that which is thus carried, across space and through time. Translation always comes after. But, writes Walter Benjamin, it harbors the potential to powerfully affect the mother tongue. It may activate a space where reciprocity trembles in the passage between here and there, now and then. Spending time with Lukin Linklater’s subtle and complex work, I think it does more than activate a space, though:The Harvest Sturdies creates a space where bodies move through poems and, for a little while, enter into a space in-between stories told, read, held, heard, carried, danced, and felt.