Tetsuya Yamada: Untie

Review I by Sara Nichol

Denler Gallery

Oct 6–Nov 4, 2016

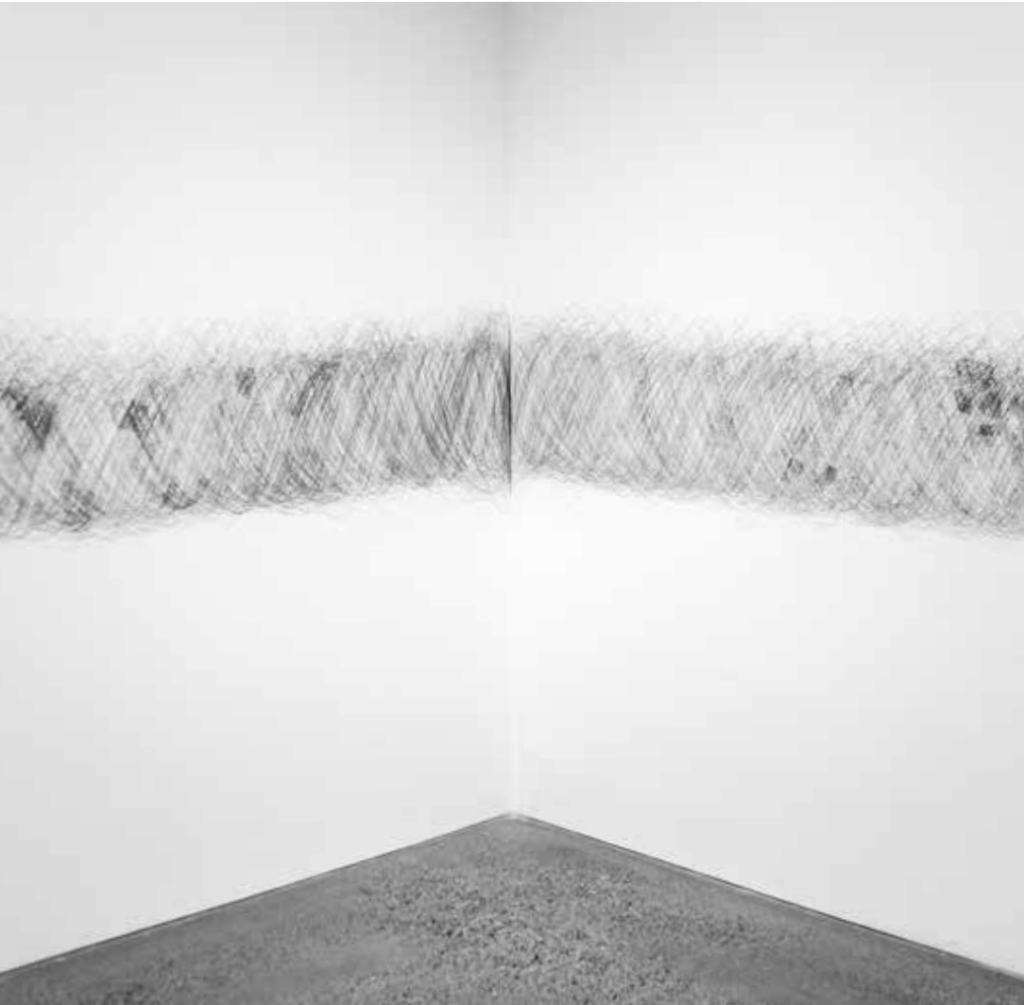

The lights were off in the Denler Gallery the first time I visited. I entered the empty gallery unsure if the dimness was intentional and walked around the circumference of the room. My path through the space is led by marks along each wall: torso-high pencil lines in sinusoidal waves illustrate that this path has been walked before, many times.

The hundreds of lines all follow the same pattern and are within the same bounds, but begin at different points. The artists’ stride and quickness of the movement of his arm determine the intensity of the waves. Each line seems purposeful, but not controlled or calculated. Over time and rotations around the room, the waves build up into a wide, hazy, horizontal border bisecting every wall.

I turn the lights on to half-power. The dimness before added a meditative quality and obscurity to the space, but the light now illuminates the work in the center of the room: a young tree, branches and top snipped. Branches lower on the trunk have been cut short while towards the top a few extend enough to show their odd growth patterns: one curves up, one horizontally out and then a slight downturn, the other an upright diagonal arm of a Y. Each branch is distinct and bodily.

A rope is delicately tied in place at the end of two limbs and hangs loosely, drooping between these high branches. Stiff circles of rope, some partially dyed a faded black, hang from the tethered swoop and collect together as their weight pulls the lowest point of the sweeping bow of rope slightly off-center. Another dyed rope gently slopes down from the top of the tree to a cut limb near eye-level. At the base of the tree is a rock, about the size of a human head. Large enough to give the sense of an intimidating mass, but small enough to make one inspect more closely. It is a rock, un-manipulated.

The gallery is quiet and contemplative, my body relaxing in this kind, thoughtful space. Walking Drawing seems, at first, a representation of the mundane everyday, made of a common form. The artist is propelled forward through time as he walks along the walls. Viewers take in the scope of his actions after termination.

Yamada’s work is present in this moment, a visual representation not solely of the mundane every day, but also of significant moments—creations, endings, obstacles—tied to a history and future greater than the singular. I feel the residue of this accumulation deeply, and consider what might be left behind in my wake.

In reflecting on Yamada’s steps and lines, the repetition of the movement of his arm, and the suggestive accumulation that obscures individual marks, I consider where I am in my own life: the struggles, pain, and hurt I have internalized and left unspoken. The failures repeated, the stagnant pattern of the dayto-day, the reclusive and unproductive moments. It is much easier to dwell in the negative. Alone in this gallery, I feel the weight of these actions and inactions. I become angry, fueled by ingrained feelings of exclusion that manifested as I walked through the surrounding campus, and memories of wrought times. I want to create obstacles, like the gallery’s corners, where the fluid motion of the drawing stops and blackens upon itself. I want the struggle of making illustrated. And then I realize that this is my reaction, and, in fact, Yamada’s work not only demonstrates the struggle of making, but also of the struggle of being.

As a ceramicist, Yamada is drawn to process. In making, one learns by doing, a slow accumulation of skills that develop into mastery. The process of mastery is quiet and slow.

I appreciate the simple, rhythmic quality of Yamada walking around the room again and again, pencil in hand, the meditative consideration of the act, repeated until it becomes something other than itself. It is highs and lows, intention and chance, openness and reticence, doing and unraveling.

The artist-ascribed ceremonial pole and rock in the middle of the room are symbols not only of the qualities that they embody, but of the processes that made them and the processes they continue to endure. A rock is formed not only over time, but also from volatile heat and compression. It hardens as the chaos subsides. In its stabilized state, the rock becomes subject to its circumstance, no longer capable of growth, but susceptible to erosion. The tree, this bodily form typically read as a feminine symbol of growth, nurturance, and exchange, is representative of a visible change unlike the rock. This change is not instantaneous, but seasonal, over the course of one’s lifetime. In this space, the tree’s branches are snipped and adorned with rope, roots are guillotined. This is a bleak confrontation. These natural elements, elevated and sanctified in this space, are in conversation with the representation of time along the walls. Do you believe people are capable of change? Over time, change will happen whether by erosion or growth.

Yamada’s work gains much of its power from its subtlety and silent reverence. This quiet conversation between time, elements, circumstance, and significance feels like the work is listening, honest in the unspoken.

Walking Drawing is static from a distance, but chaotic up close. In this timeline there are anomalies in the way the wall collects the lines. Graphite takes to spackle differently—darker—making visible latent surfaces. This drawing can be read as an individual’s life and experience, as the act of one, or as the din of collective existence. The imperfect pattern of lines shows how one could logically express noise or voices overlapping, a mathematical expression of natural forces. In the commotion of lives intersecting and parting, the anomalies are significant. There is a humbling force here. The way that this space reflects viewers back to themselves but leaves them with the sense of something greater. In Yamada’s work, through repetition comes ritual: dispersed, collected in visual moments, and exalted.